People with high cholesterol live the longest. This statement seems so incredible that it takes a long time to clear one´s brainwashed mind to fully understand its importance. Yet the fact that people with high cholesterol live the longest emerges clearly from many scientific papers. Consider the finding of Dr. Harlan Krumholz of the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at Yale University, who reported in 1994 that old people with low cholesterol died twice as often from a heart attack as did old people with a high cholesterol.1 Supporters of the cholesterol campaign consistently ignore his observation, or consider it as a rare exception, produced by chance among a huge number of studies finding the opposite.

But it is not an exception; there are now a large number of findings that contradict the lipid hypothesis. To be more specific, most studies of old people have shown that high cholesterol is not a risk factor for coronary heart disease. This was the result of my search in the Medline database for studies addressing that question.2 Eleven studies of old people came up with that result, and a further seven studies found that high cholesterol did not predict all-cause mortality either.

Now consider that more than 90 % of all cardiovascular disease is seen in people above age 60 also and that almost all studies have found that high cholesterol is not a risk factor for women.2 This means that high cholesterol is only a risk factor for less than 5 % of those who die from a heart attack.

But there is more comfort for those who have high cholesterol; six of the studies found that total mortality was inverselyassociated with either total or LDL-cholesterol, or both. This means that it is actually much better to have high than to have low cholesterol if you want to live to be very old.

High Cholesterol Protects Against Infection

Many studies have found that low cholesterol is in certain respects worse than high cholesterol. For instance, in 19 large studies of more than 68,000 deaths, reviewed by Professor David R. Jacobs and his co-workers from the Division of Epidemiology at the University of Minnesota, low cholesterol predicted an increased risk of dying from gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases.3

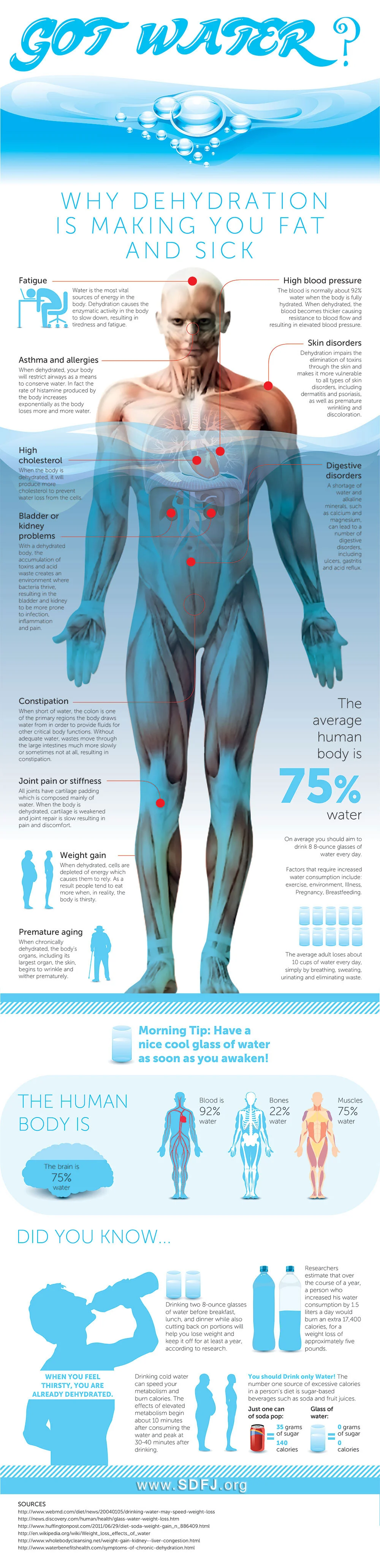

Most gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases have an infectious origin. Therefore, a relevant question is whether it is the infection that lowers cholesterol or the low cholesterol that predisposes to infection? To answer this question Professor Jacobs and his group, together with Dr. Carlos Iribarren, followed more than 100,000 healthy individuals in the San Francisco area for fifteen years. At the end of the study those who had low cholesterol at the start of the study had more often been admitted to the hospital because of an infectious disease.4,5 This finding cannot be explained away with the argument that the infection had caused cholesterol to go down, because how could low cholesterol, recorded when these people were without any evidence of infection, be caused by a disease they had not yet encountered? Isn´t it more likely that low cholesterol in some way made them more vulnerable to infection, or that high cholesterol protected those who did not become infected? Much evidence exists to support that interpretation.

Low Cholesterol and HIV/AIDS

Young, unmarried men with a previous sexually transmitted disease or liver disease run a much greater risk of becoming infected with HIV virus than other people. The Minnesota researchers, now led by Dr. Ami Claxton, followed such individuals for 7-8 years. After having excluded those who became HIV-positive during the first four years, they ended up with a group of 2446 men. At the end of the study, 140 of these people tested positive for HIV; those who had low cholesterol at the beginning of the study were twice as likely to test postitive for HIV compared with those with the highest cholesterol.6

Similar results come from a study of the MRFIT screenees, including more than 300,000 young and middle-aged men, which found that 16 years after the first cholesterol analysis the number of men whose cholesterol was lower than 160 and who had died from AIDS was four times higher than the number of men who had died from AIDS with a cholesterol above 240.7

Cholesterol and Chronic Heart Failure

Heart disease may lead to a weakening of the heart muscle. A weak heart means that less blood and therefore less oxygen is delivered to the arteries. To compensate for the decreased power, the heart beat goes up, but in severe heart failure this is not sufficient. Patients with severe heart failure become short of breath because too little oxygen is delivered to the tissues, the pressure in their veins increases because the heart cannot deliver the blood away from the heart with sufficient power, and they become edematous, meaning that fluid accumulates in the legs and in serious cases also in the lungs and other parts of the body. This condition is called congestive or chronic heart failure.

There are many indications that bacteria or other microorganisms play an important role in chronic heart failure. For instance, patients with severe chronic heart failure have high levels of endotoxin and various types of cytokines in their blood. Endotoxin, also named lipopolysaccharide, is the most toxic substance produced by Gram-negative bacteria such asEscherichia coli, Klebsiella, Salmonella, Serratia and Pseudomonas. Cytokines are hormones secreted by white blood cells in their battle with microorganisms; high levels of cytokines in the blood indicate that inflammatory processes are going on somewhere in the body.

The role of infections in chronic heart failure has been studied by Dr. Mathias Rauchhaus and his team at the Medical Department, Martin-Luther-University in Halle, Germany (Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Innere Medizin III, Martin-Luther-Universität, Halle). They found that the strongest predictor of death for patients with chronic heart failure was the concentration of cytokines in the blood, in particular in patients with heart failure due to coronary heart disease.8 To explain their finding they suggested that bacteria from the gut may more easily penetrate into the tissues when the pressure in the abdominal veins is increased because of heart failure. In accordance with this theory, they found more endotoxin in the blood of patients with congestive heart failure and edema than in patients with non-congestive heart failure without edema, and endotoxin concentrations decreased significantly when the heart’s function was improved by medical treatment.9

A simple way to test the functional state of the immune system is to inject antigens from microorganisms that most people have been exposed to, under the skin. If the immune system is normal, an induration (hard spot) will appear about 48 hours later at the place of the injection. If the induration is very small, with a diameter of less than a few millimeters, this indicates the presence of “anergy,” a reduction in or failure of response to recognize antigens. In accordance, anergy has been found associated with an increased risk of infection and mortality in healthy elderly individuals, in surgical patients and in heart transplant patients.10

Dr. Donna Vredevoe and her group from the School of Nursery and the School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles tested more than 200 patients with severe heart failure with five different antigens and followed them for twelve months. The cause of heart failure was coronary heart disease in half of them and other types of heart disease (such as congenital or infectious valvular heart disease, various cardiomyopathies and endocarditis) in the rest. Almost half of all the patients were anergic, and those who were anergic and had coronary heart disease had a much higher mortality than the rest.10

Now to the salient point: to their surprise the researchers found that mortality was higher, not only in the patients with anergy, but also in the patients with the lowest lipid values, including total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol as well as triglycerides.

The latter finding was confirmed by Dr. Rauchhaus, this time in co-operation with researchers at several German and British university hospitals. They found that the risk of dying for patients with chronic heart failure was strongly and inversely associated with total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and also triglycerides; those with high lipid values lived much longer than those with low values.11,12

Other researchers have made similar observations. The largest study has been performed by Professor Gregg C. Fonorow and his team at the UCLA Department of Medicine and Cardiomyopathy Center in Los Angeles.13 The study, led by Dr. Tamara Horwich, included more than a thousand patients with severe heart failure. After five years 62 percent of the patients with cholesterol below 129 mg/l had died, but only half as many of the patients with cholesterol above 223 mg/l.

When proponents of the cholesterol hypothesis are confronted with findings showing a bad outcome associated with low cholesterol–and there are many such observations–they usually argue that severely ill patients are often malnourished, and malnourishment is therefore said to cause low cholesterol. However, the mortality of the patients in this study was independent of their degree of nourishment; low cholesterol predicted early mortality whether the patients were malnourished or not.

Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome

As discussed in The Cholesterol Myths (see sidebar), much evidence supports the theory that people born with very high cholesterol, so-called familial hypercholesterolemia, are protected against infection. But if inborn high cholesterol protects against infections, inborn low cholesterol should have the opposite effect. Indeed, this seems to be true.

Children with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome have very low cholesterol because the enzyme that is necessary for the last step in the body’s synthesis of cholesterol does not function properly. Most children with this syndrome are either stillborn or they die early because of serious malformations of the central nervous system. Those who survive are imbecile, they have extremely low cholesterol and suffer from frequent and severe infections. However, if their diet is supplemented with pure cholesterol or extra eggs, their cholesterol goes up and their bouts of infection become less serious and less frequent.14

Laboratory Evidence

Laboratory studies are crucial for learning more about the mechanisms by which the lipids exert their protective function. One of the first to study this phenomenon was Dr Sucharit Bhakdi from the Institute of Medical Microbiology, University of Giessen (Institut für Medizinsche Mikrobiologie, Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen), Germany along with his team of researchers from various institutions in Germany and Denmark.15

Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin is the most toxic substance produced by strains of the disease-promoting bacteria called staphylococci. It is able to destroy a wide variety of human cells, including red blood cells. For instance, if minute amounts of the toxin are added to a test tube with red blood cells dissolved in 0.9 percent saline, the blood is hemolyzed, that is the membranes of the red blood cells burst and hemoglobin from the interior of the red blood cells leaks out into the solvent. Dr. Bhakdi and his team mixed purified α-toxin with human serum (the fluid in which the blood cells reside) and saw that 90 percent of its hemolyzing effect disappeared. By various complicated methods they identified the protective substance as LDL, the carrier of the so-called bad cholesterol. In accordance, no hemolysis occurred when they mixed α-toxin with purified human LDL, whereas HDL or other plasma constituents were ineffective in this respect.

Dr. Willy Flegel and his co-workers at the Department of Transfusion Medicine, University of Ulm, and the Institute of Immunology and Genetics at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany (DRK-Blutspendezentrale und Abteilung für Transfusionsmedizin, Universität Ulm, und Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, Heidelberg) studied endotoxin in another way.16 As mentioned, one of the effects of endotoxin is that white blood cells are stimulated to produce cytokines. The German researchers found that the cytokine-stimulating effect of endotoxin on the white blood cells disappeared almost completely if the endotoxin was mixed with human serum for 24 hours before they added the white blood cells to the test tubes. In a subsequent study17 they found that purified LDL from patients with familial hypercholesterolemia had the same inhibitory effect as the serum.

LDL may not only bind and inactivate dangerous bacterial toxins; it seems to have a direct beneficial influence on the immune system also, possibly explaining the observed relationship between low cholesterol and various chronic diseases. This was the starting point for a study by Professor Matthew Muldoon and his team at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They studied healthy young and middle-aged men and found that the total number of white blood cells and the number of various types of white blood cells were significantly lower in the men with LDL-cholesterol below 160 mg/dl (mean 88.3 mg/l),than in men with LDL-cholesterol above 160 mg/l (mean 185.5 mg/l).18 The researchers cautiously concluded that there were immune system differences between men with low and high cholesterol, but that it was too early to state whether these differences had any importance for human health. Now, seven years later with many of the results discussed here, we are allowed to state that the immune-supporting properties of LDL-cholesterol do indeed play an important role in human health.

Animal Experiments

The immune systems in various mammals including human beings have many similarities. Therefore, it is interesting to see what experiments with rats and mice can tell us. Professor Kenneth Feingold at the Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and his group have published several interesting results from such research. In one of them they lowered LDL-cholesterol in rats by giving them either a drug that prevents the liver from secreting lipoproteins, or a drug that increases their disappearance. In both models, injection of endotoxin was followed by a much higher mortality in the low-cholesterol rats compared with normal rats. The high mortality was not due to the drugs because, if the drug-treated animals were injected with lipoproteins just before the injection of endotoxin, their mortality was reduced to normal.19

Dr. Mihai Netea and his team from the Departments of Internal and Nuclear Medicine at the University Hospital in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, injected purified endotoxin into normal mice, and into mice with familial hypercholesterolemia that had LDL-cholesterol four times higher than normal. Whereas all normal mice died, they had to inject eight times as much endotoxin to kill the mice with familial hypercholesterolemia. In another experiment they injected live bacteria and found that twice as many mice with familial hypercholesterolemia survived compared with normal mice.20

Other Protecting Lipids

As seen from the above, many of the roles played by LDL-cholesterol are shared by HDL. This should not be too surprising considering that high HDL-cholesterol is associated with cardiovascular health and longevity. But there is more.

Triglycerides, molecules consisting of three fatty acids linked to glycerol, are insoluble in water and are therefore carried through the blood inside lipoproteins, just as cholesterol. All lipoproteins carry triglycerides, but most of them are carried by a lipoprotein named VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein) and by chylomicrons, a mixture of emulsified triglycerides appearing in large amounts after a fat-rich meal, particularly in the blood that flows from the gut to the liver.

For many years it has been known that sepsis, a life-threatening condition caused by bacterial growth in the blood, is associated with a high level of triglycerides. The serious symptoms of sepsis are due to endotoxin, most often produced by gut bacteria. In a number of studies, Professor Hobart W. Harris at the Surgical Research Laboratory at San Francisco General Hospital and his team found that solutions rich in triglycerides but with practically no cholesterol were able to protect experimental animals from the toxic effects of endotoxin and they concluded that the high level of triglycerides seen in sepsis is a normal immune response to infection.21 Usually the bacteria responsible for sepsis come from the gut. It is therefore fortunate that the blood draining the gut is especially rich in triglycerides.

Exceptions

So far, animal experiments have confirmed the hypothesis that high cholesterol protects against infection, at least against infections caused by bacteria. In a similar experiment using injections of Candida albicans, a common fungus, Dr. Netea and his team found that mice with familial hypercholesterolemia died more easily than normal mice.22 Serious infections caused by Candida albicans are rare in normal human beings; however, they are mainly seen in patients treated with immunosuppressive drugs, but the finding shows that we need more knowledge in this area. However, the many findings mentioned above indicate that the protective effects of the blood lipids against infections in human beings seem to be greater than any possible adverse effects.

Cholesterol as a Risk Factor

Most studies of young and middle-aged men have found high cholesterol to be a risk factor for coronary heart disease, seemingly a contradiction to the idea that high cholesterol is protective. Why is high cholesterol a risk factor in young and middle-aged men? A likely explanation is that men of that age are often in the midst of their professional career. High cholesterol may therefore reflect mental stress, a well-known cause of high cholesterol and also a risk factor for heart disease. Again, high cholesterol is not necessarily the direct cause but may only be a marker. High cholesterol in young and middle-aged men could, for instance, reflect the body’s need for more cholesterol because cholesterol is the building material of many stress hormones. Any possible protective effect of high cholesterol may therefore be counteracted by the negative influence of a stressful life on the vascular system.

Response to Injury

In 1976 one of the most promising theories about the cause of atherosclerosis was the Response-to-Injury Hypothesis, presented by Russell Ross, a professor of pathology, and John Glomset, a professor of biochemistry and medicine at the Medical School, University of Washington in Seattle.23,24 They suggested that atherosclerosis is the consequence of an inflammatory process, where the first step is a localized injury to the thin layer of cells lining the inside of the arteries, the intima. The injury causes inflammation and the raised plaques that form are simply healing lesions.

Their idea is not new. In 1911, two American pathologists from the Pathological Laboratories, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Oskar Klotz and M.F. Manning, published a summary of their studies of the human arteries and concluded that “there is every indication that the production of tissue in the intima is the result of a direct irritation of that tissue by the presence of infection or toxins or the stimulation by the products of a primary degeneration in that layer.”25 Other researchers have presented similar theories.26

Researchers have proposed many potential causes of vascular injury, including mechanical stress, exposure to tobacco fumes, high LDL-cholesterol, oxidized cholesterol, homocysteine, the metabolic consequences of diabetes, iron overload, copper deficiency, deficiencies of vitamins A and D, consumption of trans fatty acids, microorganisms and many more. With one exception, there is evidence to support roles for all of these factors, but the degree to which each of them participates remains uncertain. The exception is of course LDL-cholesterol. Much research allows us to exclude high LDL-cholesterol from the list. Whether we look directly with the naked eye at the inside of the arteries at autopsy, or we do it indirectly in living people using x-rays, ultrasound or electron beams, no association worth mentioning has ever been found between the amount of lipid in the blood and the degree of atherosclerosis in the arteries. Also, whether cholesterol goes up or down, by itself or due to medical intervention, the changes of cholesterol have never been followed by parallel changes in the atherosclerotic plaques; there is no dose-response. Proponents of the cholesterol campaign often claim that the trials indeed have found dose-response, but here they refer to calculations between the mean changes of the different trials with the outcome of the whole treatment group. However, true dose-response demands that the individual changes of the putative causal factor are followed by parallel, individual changes of the disease outcome, and this has never occurred in the trials where researchers have calculated true dose-response.

A detailed discussion of the many factors accused of harming the arterial endothelium is beyond the scope of this article. However, the protective role of the blood lipids against infections obviously demands a closer look at the alleged role of one of the alleged causes, the microorganisms.

Is Atherosclerosis an Infectious Disease?

For many years scientists have suspected that viruses and bacteria, in particular cytomegalovirus and Chlamydia pneumonia (also named TWAR bacteria) participate in the development of atherosclerosis. Research within this area has exploded during the last decade and by January 2004, at least 200 reviews of the issue have been published in medical journals. Due to the widespread preoccupation with cholesterol and other lipids, there has been little general interest in the subject, however, and few doctors know much about it. Here I shall mention some of the most interesting findings.26

Electron microscopy, immunofluorescence microscopy and other advanced techniques have allowed us to detect microorganisms and their DNA in the atherosclerotic lesions in a large proportion of patients. Bacterial toxins and cytokines, hormones secreted by the white blood cells during infections, are seen more often in the blood from patients with recent heart disease and stroke, in particular during and after an acute cardiovascular event, and some of them are strong predictors of cardiovascular disease. The same is valid for bacterial and viral antibodies, and a protein secreted by the liver during infections, named C-reactive protein (CRP), is a much stronger risk factor for coronary heart disease than cholesterol.

Clinical evidence also supports this theory. During the weeks preceding an acute cardiovascular attack many patients have had a bacterial or viral infection. For instance, Dr. Armin J. Grau from the Department of Neurology at the University of Heidelberg and his team asked 166 patients with acute stroke, 166 patients hospitalized for other neurological diseases and 166 healthy individuals matched individually for age and sex about recent infectious disease. Within the first week before the stroke, 37 of the stroke patients, but only 14 of the control individuals had had an infectious disease. In half of the patients the infection was of bacterial origin, in the other half of viral origin.27

Similar observations have been made by many others, for patients with acute myocardial infarction (heart attack). For instance, Dr. Kimmo J. Mattila at the Department of Medicine, Helsinki University Hospital, Finland, found that 11 of 40 male patients with an acute heart attack before age 50 had an influenza-like infection with fever within 36 hours prior to admittance to hospital, but only 4 out of 41 patients with chronic coronary disease (such as recurrent angina or pervious myocardial infarction) and 4 out of 40 control individuals without chronic disease randomly selected from the general population.28

Attempts have been made to prevent cardiovascular disease by treatment with antibiotics. In five trials treatment of patients with coronary heart disease using azithromyzin or roxithromyzin, antibiotics that are effective against Chlamydiapneumonia,yielded successful results; a total of 104 cardiovascular events occurred among the 412 non-treated patients, but only 61 events among the 410 patients in the treatment groups.28a-e In one further trial a significant decreased progression of atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries occurred with antibiotic treatment.28f However, in four other trials,30a-d one of which included more than 7000 patients,28d antibiotic treatment had no significant effect.

The reason for these inconsistent results may be that the treatment was too short (in one of the trials treatment lasted only five days). Also, Chlamydia pneumonia, the TWAR bacteria, can only propagate inside human cells and when located in white blood cells they are resistant to antibiotics.31 Treatment may also have been ineffective because the antibiotics used have no effect on viruses. In this connection it is interesting to mention a controlled trial performed by Dr. Enrique Gurfinkel and his team from Fundación Favaloro in Buenos Aires, Argentina.32 They vaccinated half of 301 patients with coronary heart disease against influenza, a viral disease. After six months 8 percent of the control patients had died, but only 2 percent of the vaccinated patients. It is worth mentioning that this effect was much better than that achieved by any statin trial, and in a much shorter time.

Does High Cholesterol Protect Against Cardiovascular Disease?

Apparently, microorganisms play a role in cardiovascular disease. They may be one of the factors that start the process by injuring the arterial endothelium. A secondary role may be inferred from the association between acute cardiovascular disease and infection. The infectious agent may preferably become located in parts of the arterial walls that have been previously damaged by other agents, initiating local coagulation and the creation of a thrombus (clot) and in this way cause obstruction of the blood flow. But if so, high cholesterol may protect against cardiovascular disease instead of being the cause!

In any case, the diet-heart idea, with its demonizing of high cholesterol, is obviously in conflict with the idea that high cholesterol protects against infections. Both ideas cannot be true. Let me summarize the many facts that conflict with the idea that high cholesterol is bad.

If high cholesterol were the most important cause of atherosclerosis, people with high cholesterol should be more atherosclerotic than people with low cholesterol. But as you know by now this is very far from the truth.

If high cholesterol were the most important cause of atherosclerosis, lowering of cholesterol should influence the atherosclerotic process in proportion to the degree of its lowering.

But as you know by now, this does not happen.

If high cholesterol were the most important cause of cardiovascular disease, it should be a risk factor in all populations, in both sexes, at all ages, in all disease categories, and for both heart disease and stroke. But as you know by now, this is not the case

I have only two arguments for the idea that high cholesterol is good for the blood vessels, but in contrast to the arguments claiming the opposite they are very strong. The first one stems from the statin trials. If high cholesterol were the most important cause of cardiovascular disease, the greatest effect of statin treatment should have been seen in patients with the highest cholesterol, and in patients whose cholesterol was lowered the most. Lack of dose-response cannot be attributed to the knowledge that the statins have other effects on plaque stabilization, as this would not have masked the effect of cholesterol-lowering considering the pronounced lowering that was achieved. On the contrary, if a drug that effectively lowers the concentration of a molecule assumed to be harmful to the cardiovascular system and at the same time exerts several beneficial effects on the same system, a pronounced dose-response should be seen.

On the other hand, if high cholesterol has a protective function, as suggested, its lowering would counterbalance the beneficial effects of the statins and thus work against a dose-response, which would be more in accord with the results from the various trials.

I have already mentioned my second argument, but it can’t be said too often: High cholesterol is associated with longevity in old people. It is difficult to explain away the fact that during the period of life in which most cardiovascular disease occurs and from which most people die (and most of us die from cardiovascular disease), high cholesterol occurs most often in people with the lowest mortality. How is it possible that high cholesterol is harmful to the artery walls and causes fatal coronary heart disease, the commonest cause of death, if those whose cholesterol is the highest, live longer than those whose cholesterol is low?

To the public and the scientific community I say, “Wake up!”

Sidebars

Risk Factor

There is one risk factor that is known to be certain to cause death. It is such a strong risk factor that it has a 100 percent mortality rate. Thus I can guarantee that if we stop this risk factor, which would take no great research and cost nothing in monetary terms, within a century human deaths would be completely eliminated. This risk factor is called “Life.”

Barry Groves, www.second-opinions.co.uk.

Familial Hypercholesterolemia – Not as Risky as You May Think

Many doctors believe that most patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) die from CHD at a young age. Obviously, they do not know the surprising finding of the Scientific Steering Committee at the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford, England. For several years, these researchers followed more than 500 FH patients between the ages of 20 and 74 and compared patient mortality during this period with that of the general population.

During a three- to four-year period, six of 214 FH patients below age 40 died from CHD. This may not seem particularly frightening but as it is rare to die from CHD before the age of 40, the risk for these FH patients was almost 100 times that of the general population.

During a four- to five-year period, eight of 237 FH patients between ages 40 and 59 died, which was five times more than the general population. But during a similar period of time, only one of 75 FH patients between the ages of 60 and 74 died from CHD, when the expected number was two.

If these results are typical for FH, you could say that between ages 20 and 59, about 3 percent of the patients die from CHD, and between ages 60 and 74, less than 2 percent die, in both cases during a period of 3-4 years. The authors stressed that the patients had been referred because of a personal or family history of premature vascular disease and therefore were at a particularly high risk for CHD. Most patients with FH in the general population are unrecognized and untreated. Had the patients studied been representative for all FH patients, their prognosis would probably have been even better.

This view was recently confirmed by Dr. Eric Sijbrands and his coworkers from various medical departments in Amsterdam and Leiden, Netherlands. Out of a large group they found three individuals with very high cholesterol. A genetic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of FH and by tracing their family members backward in time, they came up with a total of 412 individuals. The coronary and total mortality of these members were compared with the mortality of the general Dutch population.

The striking finding was that those who lived during the 19th and early 20th century had normal mortality and lived a normal life span. In fact, those living in the 19th century had a lower mortality than the general population. After 1915 the mortality rose to a maximum between 1935 and 1964, but even at the peak, mortality was less than twice as high as in the general population.

Again, very high cholesterol levels alone do not lead to a heart attack. In fact, high cholesterol may even be protective against other diseases. This was the conclusion of Dr. Sijbrands and his colleagues. As support they cited the fact that genetically modified mice with high cholesterol are protected against severe bacterial infections.

“Doctor, don’t be afraid because of my high cholesterol.” These were the words of a 36-year-old lawyer who visited me for the first time for a health examination. And indeed, his cholesterol was high, over 400 mg/dl.

“My father’s cholesterol was even higher,” he added. “But he lived happily until he died at age 79 from cancer. And his brother, who also had FH, died at age 83. None of them ever complained of any heart problems.” My “patient” is now 53, his brother is 56 and his cousin 61. All of them have extremely high cholesterol values, but none of them has any heart troubles, and none of them has ever taken cholesterol-lowering drugs.

So, if you happen to have FH, don’t be too anxious. Your chances of surviving are pretty good, even surviving to old age.

Scientific Steering Committee on behalf of the Simon Broome Register Group. Risk of fatal coronary heart disease in familial hypercholesterolaemia. British Medical Journal 303, 893-896, 1991; Sijbrands EJG and others. Mortality over two centuries in large pedigree with familial hypercholesterolaemia: family tree mortality study. British Medical Journal 322, 1019-1023, 2001.

From The Cholesterol Myths by Uffe Ravnvskov, MD, PhD, NewTrends Publishing, pp 64-65.

References

- Krumholz HM and others. Lack of association between cholesterol and coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity and all-cause mortality in persons older than 70 years. Journal of the American Medical Association 272, 1335-1340, 1990.

- Ravnskov U. High cholesterol may protect against infections and atherosclerosis. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 96, 927-934, 2003.

- Jacobs D and others. Report of the conference on low blood cholesterol: Mortality associations. Circulation 86, 1046–1060, 1992.

- Iribarren C and others. Serum total cholesterol and risk of hospitalization, and death from respiratory disease.International Journal of Epidemiology 26, 1191–1202, 1997.

- Iribarren C and others. Cohort study of serum total cholesterol and in-hospital incidence of infectious diseases.Epidemiology and Infection 121, 335–347, 1998.

- Claxton AJ and others. Association between serum total cholesterol and HIV infection in a high-risk cohort of young men. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes and human retrovirology 17, 51–57, 1998.

- Neaton JD, Wentworth DN. Low serum cholesterol and risk of death from AIDS. AIDS 11, 929–930, 1997.

- Rauchhaus M and others. Plasma cytokine parameters and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure.Circulation 102, 3060-3067, 2000.

- Niebauer J and others. Endotoxin and immune activation in chronic heart failure. Lancet 353, 1838-1842, 1999.

- Vredevoe DL and others. Skin test anergy in advanced heart failure secondary to either ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. American Journal of Cardiology 82, 323-328, 1998.

- Rauchhaus M, Coats AJ, Anker SD. The endotoxin-lipoprotein hypothesis. Lancet 356, 930–933, 2000.

- Rauchhaus M and others. The relationship between cholesterol and survival in patients with chronic heart failure.Journal of the American College of Cardiology 42, 1933-1940, 2003.

- Horwich TB and others. Low serum total cholesterol is associated with marked increase in mortality in advanced heart failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure 8, 216-224, 2002.

- Elias ER and others. Clinical effects of cholesterol supplementation in six patients with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS). American Journal of Medical Genetics 68, 305–310, 1997.

- Bhakdi S and others. Binding and partial inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus a-toxin by human plasma low density lipoprotein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 258, 5899-5904, 1983.

- Flegel WA and others. Inhibition of endotoxin-induced activation of human monocytes by human lipoproteins.Infection and Immunity 57, 2237-2245, 1989.

- Weinstock CW and others. Low density lipoproteins inhibit endotoxin activation of monocytes. Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis 12, 341-347, 1992.

- Muldoon MF and others. Immune system differences in men with hypo- or hypercholesterolemia. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology 84, 145-149, 1997.

- Feingold KR and others. Role for circulating lipoproteins in protection from endotoxin toxicity. Infection and Immunity 63, 2041-2046, 1995.

- Netea MG and others. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice are protected against lethal endotoxemia and severe gram-negative infections. Journal of Clinical Investigation 97, 1366-1372, 1996.

- Harris HW, Gosnell JE, Kumwenda ZL. The lipemia of sepsis: triglyceride-rich lipoproteins as agents of innate immunity. Journal of Endotoxin Research 6, 421-430, 2001.

- Netea MG and others. Hyperlipoproteinemia enhances susceptibility to acute disseminated Candida albicans infection in low-density-lipoprotein-receptor-deficient mice. Infection and Immunity 65, 2663-2667, 1997.

- Ross R, Glomset JA. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine 295, 369-377, 1976.

- Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and update. New England Journal of Medicine 314, 488-500, 1986.

- Klotz O, Manning MF. Fatty streaks in the intima of arteries. Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology. 16, 211-220, 1911.

- At least 200 reviews about the role of infections in atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease have been published; here are a few of them: a) Grayston JT, Kuo CC, Campbell LA, Benditt EP. Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR and atherosclerosis. European Heart Journal Suppl K, 66-71, 1993. b) Melnick JL, Adam E, Debakey ME. Cytomegalovirus and atherosclerosis. European Heart Journal Suppl K, 30-38, 1993. c) Nicholson AC, Hajjar DP. Herpesviruses in atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Etiologic agents or ubiquitous bystanders? Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology 18, 339-348, 1998. d) Ismail A, Khosravi H, Olson H. The role of infection in atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. A new therapeutic target. Heart Disease 1, 233-240, 1999. e) Kuvin JT, Kimmelstiel MD. Infectious causes of atherosclerosis. f.) Kalayoglu MV, Libby P, Byrne GI. Chlamydia pneumoniaas an emerging risk factor in cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American Medical Association 288, 2724-2731, 2002.

- Grau AJ and others. Recent bacterial and viral infection is a risk factor for cerebrovascular ischemia. Neurology 50, 196-203, 1998.

- Mattila KJ. Viral and bacterial infections in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Internal Medicine225, 293-296, 1989.

- The successful trials: a) Gurfinkel E. Lancet 350, 404-407, 1997. b) Gupta S and others. Circulation 96, 404-407, 1997. c) Muhlestein JB and others. Circulation 102, 1755-1760, 2000. d) Stone AFM and others. Circulation 106, 1219-1223, 2002. e) Wiesli P and others. Circulation 105, 2646-2652, 2002. f) Sander D and others. Circulation106, 2428-2433, 2002.

- The unsuccessful trials: a) Anderson JL and others. Circulation 99, 1540-1547, 1999. b) Leowattana W and others.Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 84 (Suppl 3), S669-S675, 2001. c) Cercek B and others. Lancet 361, 809-813, 2003. d) O’Connor CM and others. Journal of the American Medical Association. 290, 1459-1466, 2003.

- Gieffers J and others. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in circulating human monocytes is refractory to antibiotic treatment. Circulation 104, 351-356, 2001

- Gurfinkel EP and others. Circulation 105, 2143-2147, 2002.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly magazine of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Spring 2004.